How To Beat Kaggle (the Easy Way)

A few nights ago, I found myself tinkering with the Titanic data set on Kaggle and couldn’t help but notice the number of people with a perfect score – many of whom have a single entry.

So, I thought to myself: “Clearly, they must be cheating. But how do you cheat efficiently?”

A Mathematician’s Perspective

The Kaggle competition ‘Titanic: Machine Learning from Disaster’ (and in fact any classification competition on Kaggle) can be modelled as follows:

Kaggle asks you to find a secret \(n\)-dimensional vector \(\vec{k} = (k_1, k_2, \ldots, k_n)\) (with \(n=418\) for the Titanic data set) where each number \(k_i\) is either \(0\) (the passenger with ID \(i\) didn’t survive) or \(1\) (the passenger with ID \(i\) did survive). So all we really have to do is to guess \(\vec{k}\) – no need for fancy machine learning techniques!

There are \(2^n\) many possible values for \(\vec{k}\) and guessing all of them would be practically impossible. Fortunately, there’s one more ingredient to Kaggle that we can exploit: If we submit a guess \(\vec{g} = (g_1, \ldots, g_n)\) to Kaggle, it will return a score – the number of correct guesses. I.e. the number of \(i\)s such that \(g_i = k_i\).

A Naive Approach

This allows for a naive solution in (at most) \(n+1\) many guesses: First guess \(\vec{g}_0 = (0,0, \ldots, 0)\) resulting in a score of correct entries \(s_0\) and then, for each \(i = 1, \ldots, n\) guess \(\vec{g}_i\) – the binary vector with only one \(1\) in position \(i\). Let \(s_i\) be the resulting score. If \(s_i > s_0\), then the \(i\)th entry of \(\vec{k}\) must be a \(1\). Otherwise it is a \(0\).

While this is certainly possible to pull off in practice 1, it does not satisfy my urge for efficiency.

Can we do better?

Indeed! But making significant progress will require some work.

Insert Graph Theory

Definition

Let \(G = (V;E)\) be an undirected graph. Let \(u,v \in V\) be vertices. The distance \(d_G(v,u)\) of \(v\) and \(u\) in \(G\) (in symbols \(d_G(u,v)\)) is the length of the minimal path of edges in \(G\) that connects \(v\) and \(u\). If no such path exists, we let \(d_G(v,u) := \infty\). 2

Definition

Let \(G = (V;E)\) be an undirected graph and let \(R \subseteq V\) be a set of vertices. \(R = \{r_1, \ldots, r_k \}\) resolves \(G\) if every vertex \(v \in V\) is uniquely determined by its vector of distances to members of \(R\). To put it in mathematical terms: \(R\) resolves \(G\) if the function

\[ d_R \colon V \to [0, \infty]^k, v \mapsto (d_G(v,r_1), d_G(v,r_2), \ldots, d_G(v,r_k)) \]

is injective.

Note that \(R = V = \{ v_1, \ldots, v_n \}\) trivially resolves \(G\) as every \(v \in V\) is uniquely determined by \(i \in \{1, \ldots, n \}\) with \(d_G(v,v_i) = 0\) since in this case we have \(v = v_i\).

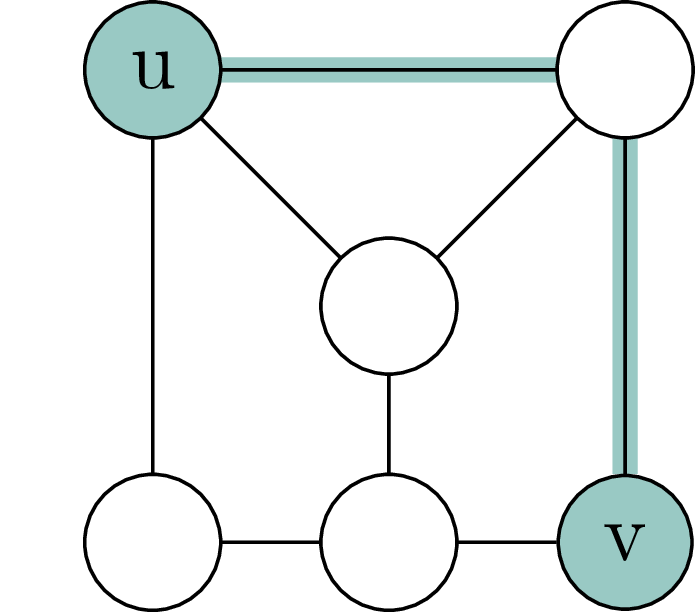

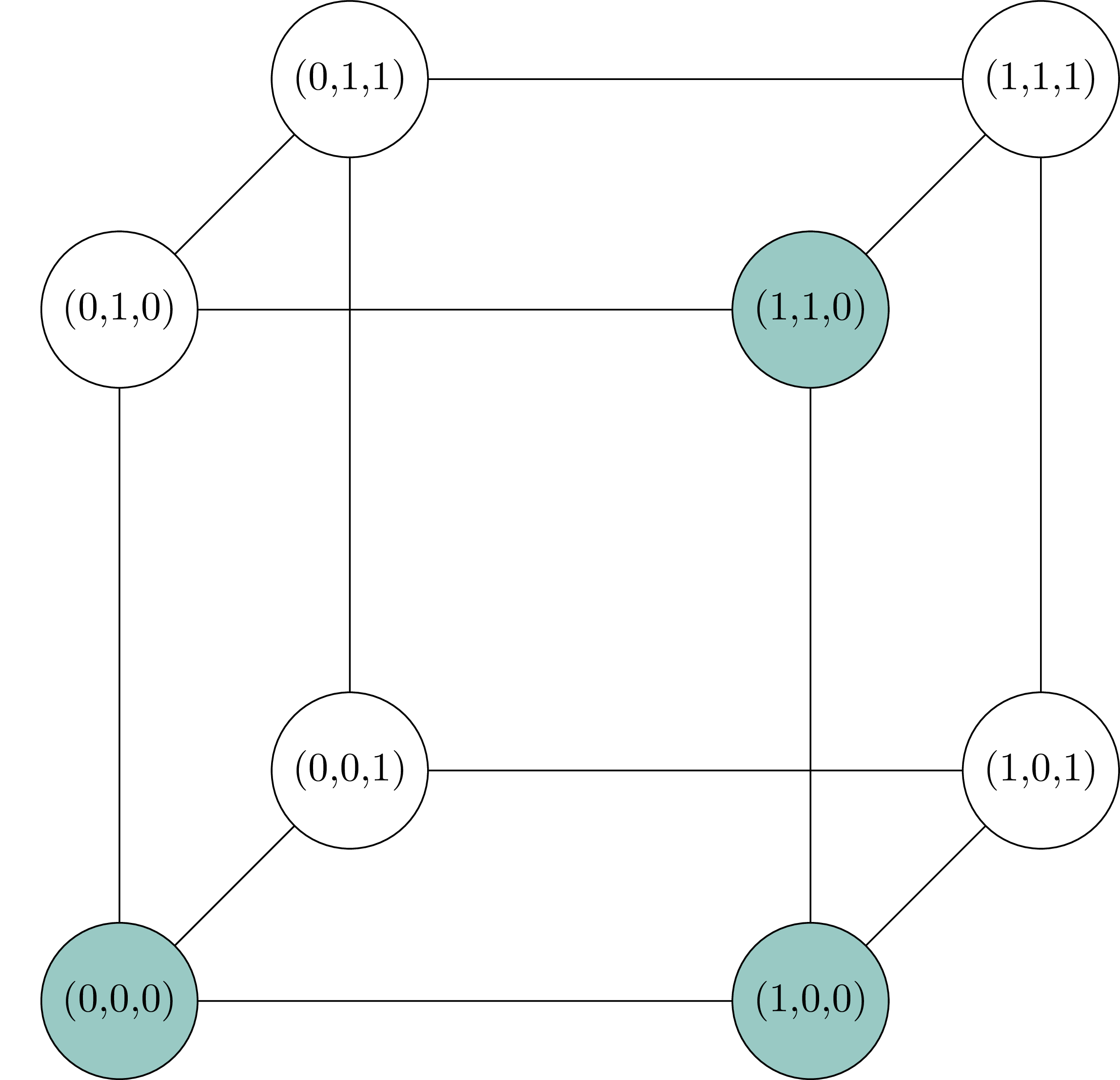

Consider the following example:

Here, the vertex \((0,1,1)\) is uniquely identified by having distance \(2\) to \(r_1 = (0,0,0)\), distance \(3\) to \(r_2 = (1,0,0)\) and distance \(2\) to \(r_3 = (1,1,0)\). In other words, \((0,1,1)\) is the unique vertex with distance vector \(d_R(0,1,1) = (2,3,2)\) to the highlighted resolving set.

I encourage the reader to check that \(R = \{ (0,0,0), (1,0,0), (1,1,0) \}\) is indeed a resolving set for \(H(3)\) to get a better feel for this rather abstract concept before moving on.

Definition

Let \(G = (V;E)\) be an undirected graph. The metric dimension of \(G\) is the minimal size of some \(R \subseteq V\) that resolves \(G\).

Returning to our example \(H(3)\): We’ve already found a resolving set of size \(3\) and a bit of computation confirms that there is no resolving set of size \(2\). Therefore the metric dimension of \(H(3)\) is \(3\).

It is now time to meet the hero of our advanced guessing strategy.

Definition

The \(n\)-dimensional Hamming graph is the undirected graph \(H(n) = (V;E)\) whose vertices are all \(n\)-dimensional binary vectors \(\vec{v} = (v_1, \ldots, v_n)\) such that \(\{\vec{v},\vec{u}\} \in E\) iff they differ in exactly one position, i.e.

\[ E = \{ \{ \vec{v}, \vec{u} \} \mid \{i \mid v_i \neq u_i \} \text{ has size 1 } \}. \]

If you look back to the diagram of \(H(3)\), you will see that this is indeed the \(3\)-dimensional Hamming graph. Its vertices are binary vectors of length \(3\) and they are connected via a single edge if and only if they differ in exactly one coordinate.

A Graph Theoretic Guessing Strategy

Here is our graph theoretic guessing strategy: Let \(R\) be a small resolving set for \(H(n)\). Submit each \(\vec{r} \in R\) as a guess to Kaggle which sends back its score \(s(\vec{r})\). If \(s(\vec{r}) = n\) for some \(\vec{r}\), we’ve achieved a perfect score and are done with this competition. Otherwise, since \(R\) is a resolving set, there is a unique vertex \(\vec{g}\) in \(H(n)\) such that

\[ d_{H(n)}(\vec{g},\vec{r}) = n - s(\vec{r}) \]

for all \(\vec{r} \in R\).

However, by the construction of \(H(n)\), we have \(d_{H(n)} (\vec{k},\vec{r}) = n - s(\vec{r})\) (where \(\vec{k}\) is Kaggle’s secret solution vector) for all \(\vec{r} \in R\).

Since \(\vec{g}\) is the unique vector with this property, we must have that \(\vec{g} = \vec{k}\) is the desired solution. This strategy therefore guarantees a perfect score in at most \(\mathrm{size(R)} + 1\) many submissions!

Now, because \(H(n)\) has a metric dimension of \(\frac{(2+ o(1))n}{\log_2(n)}\), we will be able to crack the Titanic dataset in \(\sim 97\) 3 submissions and furthermore, if we commit to submitting all but the final guess at once, this is known to be an optimal guessing strategy.

Confessions

While this graph theoretic approach to beat Kaggle, from a purely mathematical point of view, is very pleasing, it doesn’t seem that practical after all. For instance, while the metric dimension of \(H(n)\) is known asymptotically, it’s not clear to me how to find small resolving sets for \(H(n)\) in practice. Furthermore, even if you were given a small resolving set \(R\), calculating \(\vec{k}\) from \(\{ d_{H(n)}(\vec{k}, \vec{r}) \mid \vec{r} \in R \}\) requires some serious computational power. Granted, it doesn’t increase the number of guesses required, the metric I’ve chosen to optimize for, but it still results in so much computational overhead that the naive approach will win out.

What’s worse: We are not taking full advantage of Kaggle’s feedback to our guesses. When guessing the entries of our resolving set one by one, we don’t use the information gained to guide our future guesses. Instead we could just as well have submitted them all in one go, collect the scores and then compute the correct solution. If we add this further restriction, the solution presented here is optimal. However, without this artificial restriction, I suspect that a better performing, general solution should be possible and I’d very much like to find one.

In practice, if you want to do better than this graph theoretic guessing strategy, I’d suggest cooking up a reasonably well-performing model. You then adapt the naive approach by prioritizing those bits that your model is least certain about. This, if I had to guess, is what people actually do to obtain perfect scores. Finally, to get a perfect score with a single entry, just calculate the solution on a different account and, once you’ve obtained it, submit it on your main account.

From Kaggle’s point of view, at least in the case of the Titanic dataset, this attack vector is pretty much impossible to defend against. For larger datasets, on the other hand, there certainly is a lot they can do to prevent successful guessing strategies. That, however, is a story for another day…

Sources

- Math Overflow. Guessing a subset of \(\{1, \ldots, N \}\)

- Jian, Polyanskii. How to guess an \(n\)-digit number

- Jian, Polyanksii. On the metric dimension of Cartesian powers of a graph

- Caceres, Puertas. ON THE METRIC DIMENSION OFCARTESIAN PRODUCTS OF GRAPHS

- Caceres, Hernando, Mora, Pelayo, Puertas, Seara and Wood. ON THE METRIC DIMENSION OF CARTESIAN PRODUCTS OF GRAPHS

- Bernt Lindström. On a combinatory detection problem. I (Magyar Tud. Akad.Mat. Kutato Int. Közl., 9:195–207, 1964)

- Math Overflow. Explicit, small resolving sets for Hamming graphs

-

Kaggle’s daily submission limit poses only the tiniest of hurdles to any programmer… ↩

-

\(d_G\) is the usual graph metric ↩

-

The exact number depends on the precise metric dimension of \(H(418)\) which I do not yet know at the time of writing this post. All I know for certain is that it is \(\le 418\). ↩